Aziz Isa Elkun

If one of London´s Uyghurs happens to be looking through London´s A to Z street map and stumbles upon the entry: Kashgar Road, it is with a shock of recognition. For London´s Uyghurs, used to the daily routine of explaining to the British who the Uyghurs are and where they come from, it is extraordinary to find that one of their major cities has lent its name to a London street. How did this come about?

If one of London´s Uyghurs happens to be looking through London´s A to Z street map and stumbles upon the entry: Kashgar Road, it is with a shock of recognition. For London´s Uyghurs, used to the daily routine of explaining to the British who the Uyghurs are and where they come from, it is extraordinary to find that one of their major cities has lent its name to a London street. How did this come about?

The city of Kashgar is situated in distant Asia, today a little known city, it was a capital of the Uyghur Qarakhan Kingdom in the 11th century and a political and cultural centre for the Central Asian Uyghurs. Kashgar means in the Uyghur Turkic language: the city at the river bank (Zerepshan river) and its geographical location is between the eastern foothills of the Pamir-Karakorum mountain range and the west edge of the Taklamakan desert, and its present position on the political map is within the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Northwest China.

The London district of Plumstead lies to the east of the city, on the south bank of the river Thames, bordering on the industrial centre of Woolwich. Until the 19th century it was a small village whose thousand or so inhabitants made a living from fishing and agriculture; the name Plumstead means ´the place where the plums grow´. In the mid 19th century this changed suddenly and this small Kentish village mushroomed into a heavily populated London suburb. In 1841 the population of Plumstead was 2,816 but by 1891 it had grown to 52,754.

Plumstead´s sudden growth in the 19th century was inextricably linked to Woolwich, its imperial and military connections, and in particular its importance as a centre for the manufacture of arms and armaments. The site where this took place was given the name Royal Arsenal in 1805. Woolwich was also a major garrison town, housing thousands of soldiers, and home to a major dockyard of the Royal Navy. The Royal Arsenal expanded in the mid-19th century in response to the ever-growing military aspect of sustaining and enlarging the British Empire.

In the second half of the 19th century Plumstead was fast becoming one huge building site. Industry in Woolwich continued to expand, spurred on in particular by the Crimean War (1854-6). The Armstrong Gun Factory, new cartridge and gun carriage factories were built on reclaimed Plumstead marshland. The British Empire and its exploits were reflected in all the stages of development in Plumstead, as befitted an area which was contributing so directly to British military expansion. The first major building development began in the 1850s around the time of the Crimean War, and the commanders and battles of that war provided names for the new

In the second half of the 19th century Plumstead was fast becoming one huge building site. Industry in Woolwich continued to expand, spurred on in particular by the Crimean War (1854-6). The Armstrong Gun Factory, new cartridge and gun carriage factories were built on reclaimed Plumstead marshland. The British Empire and its exploits were reflected in all the stages of development in Plumstead, as befitted an area which was contributing so directly to British military expansion. The first major building development began in the 1850s around the time of the Crimean War, and the commanders and battles of that war provided names for the new

streets.

Kashgar Road was part of a network of streets built in the 1870s and 1880s. Many of the roads were given similarly exotic names from far-flung parts of the empire, or areas in which Britain was then becoming interested in: Kashgar Road adjoins Benares Road, named for the ancient Indian city, while the neighbouring Ceres Road seems to have been named for a Royal Navy ship, the HMS Ceres. But apart from the names, there was little glamorous or exotic about the streets themselves. Their terraced houses were small and were aimed at the many semi-skilled and manual workers who produced the armaments at the Royal Arsenal.

So why had the Turkestani town of Kashgar come to capture the British imagination in the mid-19th century? Previously almost unknown in the West, Kashgar began to feature in the British press in the 1860s and 1870s when it was drawn into the ´Great Game´, the struggle for influence in Central Asia between the two expanding colonial powers, Britain

and Russia.

Kashgar´s appearance in the Great Game was impelled by local events, beginning with a major rebellion against the ruling Qing empire in the 1860s and the emergence of the Khoqandi General Yaqub Beg as ruler of Kashgaria. In 1865 Yaqub Beg crossed into Kashgar from Khoqand, and by 1867 he had established his rule over Kashgar and the surrounding regions. Both Britain and Russia quickly moved to exploit this potential to extend their influence in the region.

The British first sent an Indian army officer, Mirza Shuja, on an undercover mission to Kashgar in 1866. His task was to report back to Britain on political developments, and to produce reliable maps of tha

The British first sent an Indian army officer, Mirza Shuja, on an undercover mission to Kashgar in 1866. His task was to report back to Britain on political developments, and to produce reliable maps of tha

t as yet unknown region. In 1868 the first British man, the trader Robert Shaw, arrived in Kashgar from In

dia with a caravan carrying tea and other goods. Another British man George Hayward came soon after on a government mission to explore the mountain passes between Ladakh and Kashgaria. Both men were held in Kashgar for several months before Yaqub Beg sent them back with a message of friendship to the British gover

nment. The men received a heroes´ welcome when they arrived back in India, and Kashgar became the latest name to feature in British press accounts of the exploits of its brave ´sons of empire´ in dangerous and exotic regions.

The British were keenly aware that Yaqub Beg was also courting the Russians, who moved in 1871 to take control over the Ili valley to the north. Yaqub Beg also continued his conquests, and by 1872 he had expanded his territory north and east to today´s Urumchi and Qumul. In 1873 Lord Mayo, the Viceroy of India, sent a large diplomatic mission to Kashgar led by Douglas Forsythe with 350 men in his train, including cavalry, interpreters, clerks, guides and servants. Diplomatic ties were established, Britain formally recognised Yaqub Beg´s rule, and attempted to broker an agreement between the Qing and Yaqub Beg´s representatives to establish an independent buffer state between British India, Russia and China.

However, Britian´s interest in Yaqub Beg did not last. In 1876 the Qing, having successfully dealt with the Taiping uprising in inner China, sent General Zuo Zongtang to restore control over Kashgaria.

Britain decided to abandon its support of Yaqub Beg, and offered financial support to Zuo Zongtang, believing that Chinese rule in the region offered a stronger buffer against Russia. Zuo´s campaign was slow and expensive but successful. Urumchi was taken in 1876 and subjected to a bloody massacre, and the state of Kashgaria fell soon after following the death of Yaqub Beg in 1877.

In 1881 Russia returned the Ili valley to the Qing, and in 1884 the whole region was formally incorporated into the Qing Empire as Xinjiang province, but the British and Russians continued to vie for influence in Kashgar for years. By the turn of the century both powers had established consuls in Kashgar, and the British public continued to be entertained by accounts written by explorers, archaeologists and adventurers in the region over the next few decades, while Kashgar Road, Plumstead, remains as a monument to the complex politics of that time.

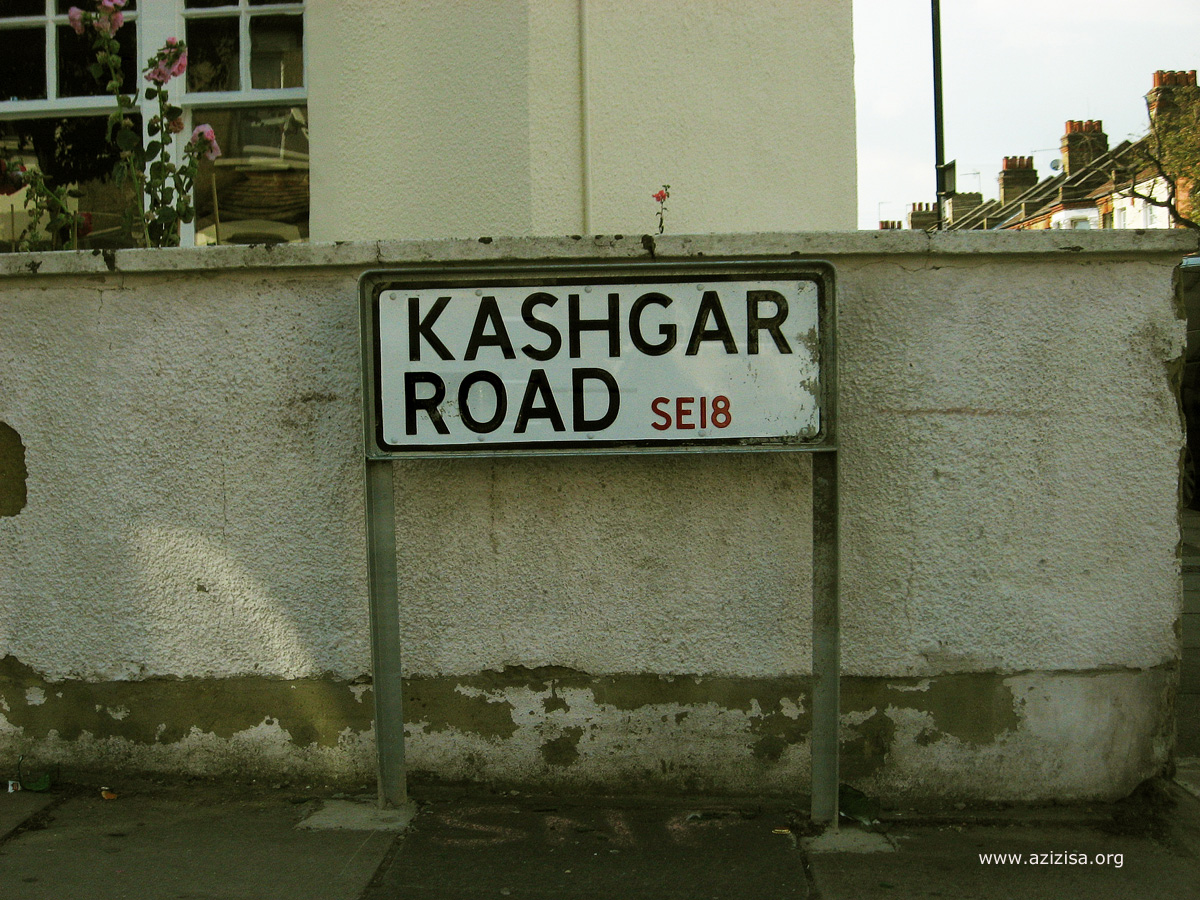

Photos from present London Kashgar Road:

References

http://www.ideal-homes.org.uk/greenwich/plumstead/plumstead-1800-1900-01.htm#BeforeDevelopment (accessed 25/6/07)

Boulger, Demetrius Charles. 1878. The life of Yakoob Beg; Athalik Ghazi, and Badaulet; Ameer of Kashgar. London: W. H. Allen & Co.

Hopkirk, Peter. 1990. The Great Game: on Secret Service in High Asia.Oxford University.

* This article is also published on the BBC Uzbek website:

http://www.bbc.com/uzbek/news/story/2008/01/080110_qeshqer_st_lat.shtml

* Read this article in Uyghur:

Hi I have found today this amazing website! Very creative, indeed! Keep up your dedicated work. Congratulation!

By the turn of the century both powers had established consuls in Kashgar, and the British public continued to be entertained by accounts written by explorers, archaeologists and adventurers in the region over the next few decades, while Kashgar Road, Plumstead, remains as a monument to the complex politics of that time.

By the turn of the century both powers had established consuls in Kashgar, and the British public continued to be entertained by accounts written by explorers, archaeologists and adventurers in the region over the next few decades, while Kashgar Road, Plumstead, remains as a monument to the complex politics of that time.